Maenads in Classical Works

| ✅ Paper Type: Free Essay | ✅ Subject: Classics |

| ✅ Wordcount: 2009 words | ✅ Published: 23 Sep 2019 |

Introduction

εἰς ὄρος εἰς ὄρος, ἔνθα μένει

θηλυγενὴς ὄχλος

ἀφ᾽ ἱστῶν παρὰ κερκίδων τ᾽

οἰστρηθεὶς Διονύσῳ.

“to the mountain, to the mountain, where there rests/ the throng of women, / driven by Dionysus in madness/ from their looms and shuttles. (Euripides, The Bacchae, 116-119 Loeb translation)

Maenads (μαϊνάδες), or Bacchants as the Romans called them, were female revellers in the cult of Dionysus (the god of wine, ecstacy and theatre), along with the Dionysian cohort of Silenus (companion and tutor to Dionysus) and mischievous satyrs. The Greek has been translated contentiously to mean, “raving ones” and was also used to refer to women beyond Dionysus’ retinue, as the term came to be associated with a wide variety of women in antiquity, from the mythological, supernatural, and historical; whose behaviour did not conform to society’s norms, such as Medea and Clytemnestra. Maenads, however, are more directly associated with religious fanaticism concerning the god Dionysus and his worship.

There were two ways in which these women were mythologized in literature; as either a follower possessed by the power of the divinity or as nurses and eventually willing attendants. Primarily, it was as the mad, wild, debauched women who went into the mountains at night and practised strange rites. The poetic, as opposed to anthropological, significance of maenads in Greek literature is illustrated above all by the occurrence of the word ‘maenad’in metaphors and similes. In epic poetry and tragedy, the image is appropriated for emotional extremes. In the Iliad, Andromache is compared to a maenad as she runs out of her house, ὣς φαμένη μεγάροιο διέσσυτο μαινάδι ἴση/ παλλομένη κραδίην (“thus she darted out of the hall as a maenad, her heart racing” 22.460-1), as the thought of her husband Hektor’s death has pushed Andromache beyond the limits of self-control. The comparison occurs in a different context in the Homeric Hymn to Demeter, as Demeter darts from her temple to greet Persephone, upon seeing her daughter safely returned from the underworld, ἠύτε μαινὰς ὄρος κάτα δάσκιον ὕλῃ (“like a maenad on a tree-covered mountain” 386). Here, however, Demeter is in the grip of joy rather than grief, but both seem to be posed by intense feeling. The 6th-century poet Anakreon referred to maenads as “Διονύσου σαῦλαι Βασσαρίδες”[1] (“the hip-swaying Bassarids”), referencing their characteristic dances of possession and madness. Maenads became more and more widely depicted from the 5th century onwards, particularly in drama, assumedly on account of Dionysus being the honorary god within the theatre. The most well-known depiction of maenads, today as well as then, was from Euripides’ play The Bacchae, written by the end of the 5th-century. It tells of how the maenads of Thebes murder King Pentheus as divine punishment after he bans the worship of Dionysus. Dionysus himself lures Pentheus to the woods, where the maenads including his mother, Agave, tear him apart limb from limb in grotesque detail, in a trance believing him to be a lion. They similarly act as dispensers of justice in the case of Orpheus, who they also tear limb from limb for not honouring the Godhead (Pseudo Apollodorus, Library and Epitome 1.3.2). More generally, myths expressing female aggression and hostility against males were common in ancient Greece, with notable figures of popularity in Greek tragedy like Medea, Clytemnestra and Phaedra. The metaphors and similes of maenads are found also in Latin literature, from Cicero during the Republic (Pro Caelio 18, 62) and Virgil in the Augustan period (Aeneid 4.301) to describe similarly deranged and uncontrollable women.

In the ancient world, there exists a body of art dedicated to Maenads and their ritual madness, religious euphoria, and theatrical representation. In this thesis, I will not touch upon the believed Maenadic followers of history (of which work has been done cf. Henrichs 1978, Fernandez 2013), but rather focus more on their artistic representation. There must be an understanding of where they came from in literature and art, and their gradual representational evolution which was already developing in the archaic and classical periods of the Greek world, to form the background of which this thesis is informed by and from which the Hellenistic period and Roman representation of the maenad develops.

From the late archaic to the early classical period onwards, maenads began to be represented in the artistic medium, much later than their attributed presence in literature. Maenads are largely identifiable through their dress of fawn skins and by carrying a thyrsus, a long stick wrapped in ivy or vine leaves and tipped with a pine cone, and occasionally weaving ivy-wreaths around their heads.

I have divided my thesis by looking at three prevalent maenadic types (the Dancing, Sleeping and Floating maenads), in an attempt to simplify their renderings within various mediums and reconstruct how we look and think of these female figures, as Sylvia Plath in her poem ‘The Maenad’ puts aptly; “Lady, who are these others in the moon’s vat — Sleepdrunk, their limbs at odds?”. The Dancing maenad and Sleeping maenad are both found in the late archaic period on kylixes and sympotic drinking cups, primarily on mainland Greece, as part of the broader iconography of the Dionysiac retinue and festivities. The Floating maenad, however, is a distinctly Roman or Pompeiian invention, found on Campanian wall painting from the 1st century CE.

I am hardly the first to focus on Maenads, as notable works include Lori-Ann Touchette’s study on the Dancing Maenad reliefs at the Metropolitan Museum in New York, looking at the interesting role of dance and the physical freedom of the maenad,[2] and Sarah McNally’s article of Maenads in Early Greek Pottery, which looks at their depiction in the all-male Greek drinking party of the symposium.[3] However, my thesis will aim to build on these previous works to look at how the depiction, context, and visual features of the Maenad changed over time, particularly within the Hellenistic and Roman Period. I hope to look at these objects differently from the way they have previously been interpreted, and rethink how we use them or take them to be. The Greek image is predominantly (although not exclusively) sympotic, whereas Roman visual culture transports her image onto a number of functions, as she is found in the domestic, funerary and monumental spheres. The archetypal image of the maenad on Greek vase painting is one of rage or debauchery, according to Eva Keuls, “The Maenads, in their most unrestrained behaviour, act like persons in an ecstatic trance: they throw back their heads; raise their arms in wild gestures; and maul animals… in the cruellest fashion and brandish their severed limbs.”[4] Popular scenes depicted showed the maenads partaking in violent and aggressive acts, which came from literature, such as the sparagmos of Pentheus from The Bacchae, as a cautionary tale of the effects of wine. One may even compare and contrast their representation with other female groups, such as the Amazons, who were also revered with cautious mysticism[5], or much later, the witches present in Robert Burns’ ‘Tam O’Shanter’.

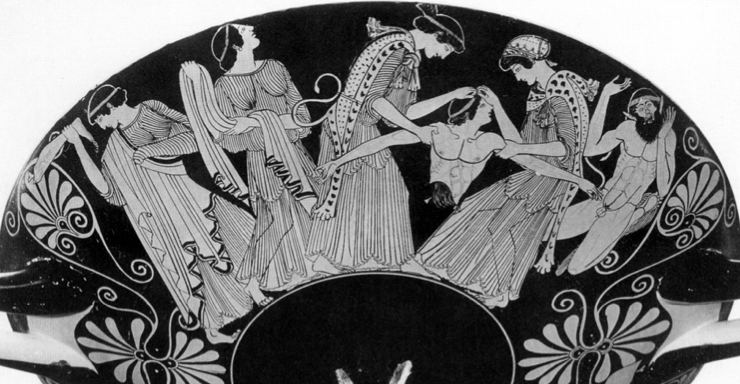

[Attic red-figure kylix representing sparagmos of Pentheus, attributed to Douris, c. 480 BCE, Kimbell Art Museum, Fort Worth TX]

[Attic red-figure kylix representing sparagmos of Pentheus, attributed to Douris, c. 480 BCE, Kimbell Art Museum, Fort Worth TX]

In Homer’s Iliad and Sophocles’ Oedipus at Colonus, there is an acknowledgement of the relationship maenads had with Dionysus, but the image is a much more caring and tender one: “ὅς ποτε μαινομένοιο Διωνύσοιο τιθήνας/ σεῦε κατ᾽ ἠγάθεον Νυσήϊον” (“he that on a time drove down over the sacred mount of Nysa the nursing mothers of mad Dionysus; and they all let fall to the ground their wands,” Il.6.132-3) and “ἀεὶ Διόνυσος ἐμβατεύει θεαῖς ἀμφιπολῶν τιθήναις.” (“Here the reveller Dionysus ever walks the ground, companion of the nymphs that nursed him” 679-680). The second (and less popular) image of the maenad presented in literature, is not as a mad reveller, taken in a drunken stupor by the god, but a carer, who nurses him. According to Plutarch’s Life of Alexander, maenads were called Mimallones and Klodones in Macedon (2.5-6), epithets derived from the feminine art of spinning wool, which is important for demonstrating that they are always in dialogue with more normative stereotypes of female behaviour. Much later, in the 5th-century CE., Nonnus, a notable Roman-Greek writer, publishes his work, The Dionysiaca. It is an epic in 48 books, composed in Homeric dialect and dactylic hexameters, centring on the life of Dionysus; his expedition to India and the culmination of his triumph of Olympus. Although Dionysus is at the fore, the maenads act in Book 9 as his nurses until Hera drives them mad, and later as warriors forming part of his army. In the Roman world, one sees the multi-faceted representation of the maenad, and how it entirely evolves, as one may find a sparagmos in one room, and the image below in another.

[A Maenad holding Cupid. Fresco from the house of Lucius Caecilius Iucundus, Pompeii; National Archaeological Museum, Naples]

[A Maenad holding Cupid. Fresco from the house of Lucius Caecilius Iucundus, Pompeii; National Archaeological Museum, Naples]

The maenad, as an isolated focal figure and as part of a larger ensemble, seems to be deeply misunderstood, both within literature and art. There seems to be no definitive answer to why maenads are sometimes drunken, wild and ferocious and at other times nursing, caring and serene, besides that of a gradual development over time. Maenads represent the flight of the Theban women into the hills, their abandonment of homes and children, and their prowess at hunting marks an inversion of the normal sex roles in Greek society. They are women but taken by divine possession, intoxication and ecstasy, beyond the bounds of civilisation and what was felt to be socially appropriate for women at the time. They aren’t motivated by revenge or scorn but act as administers of justice against those who refuse to worship Dionysus. They are entirely “Other”, and yet they are religious figures, as part of the retinue of Dionysus. It is this mystery which surrounds them, reminiscent of Aristophanes’ Thesmaphoriazusae, as a congregation of predominantly women, which was then something to be viewed simultaneously with caution, intrigue and hostility. The male intruder wonders into a space of feminine freedom and is justly punished for his intrusion.

In his article “Silens, Nymphs and Maenads”[6] Hedreen wishes for us to separate our colliding of ‘nymphs’ from ‘maenads’, but then is unable to give a valuable argument for why we should, or how the ancients themselves markedly distinguished them. Thus, the maenad could be a mortal enveloped in religious rapture, or a nymph whose relationship with the divinity becomes less and less defined. The maenad becomes, arguably much more in the Hellenistic period, a merging of both. Similarly, the image of the maenad lends itself to cross-pollination with other representations. Not only is she able to be wild and violent, but also serene and harmonious. Her representation is less one-dimensional, as below she dances, but joyfully synchronised with the satyr, as they both swing the liknon, a winnowing basket, in which the infant Bacchus lies.

[A terracotta relief of a dancing Maenad and Satyr with the infant Bacchus (Dionysus). 20 BC – 5 0 AD A Campana plaque. British Museum. GR 1805.7-3.21 (Terracotta D 525). Townley collection.]

[A terracotta relief of a dancing Maenad and Satyr with the infant Bacchus (Dionysus). 20 BC – 5 0 AD A Campana plaque. British Museum. GR 1805.7-3.21 (Terracotta D 525). Townley collection.]

Although the maenad or bacchant over time seems to retain her core features, such as partial nakedness with a covering, the carrying of a thyrsus, and wild loose hair; it is not only her context which transforms but also what she comes to represent and portray. The images surrounding these women were highly sexualised, and thus represented and displayed them as objects to be observed. Perhaps, this is retained from the early classical period to the Roman period, as she is still vulnerable to external attacks when she is asleep, is still gazed upon while dancing, and invites attention whether solitary or as a group; but the way in which people consumed and looked at her/them did, on account of her differing context and mode of representation, which as I have defined, is not so clear and disparate.

Bibliography

- Campbell, D.A., (1991), Greek Lyric Poetry, Bristol

- Hedreen, G., (1994), “Silens, Nymphs and Maenads”, Journal of Hellenic Studies

- Keuls, E.C., (1985), The Reign of the Phallus: Sexual Politics in Ancient Greece, Harpercollins

[1] Campbell.1991.pg411

[2] Touchette.(1995). The dancing Maenad reliefs: Continuity and change in Roman copies (Bulletin (Institute of Classical Studies). supplement; no 62). London: Institute of Classical Studies, UCL

[3] McNally.(1978).”The Maenad in Early Greek Art”, Arethusa

[4] Keuls.1985.pg360

[5] Apollonius Rhodius.Argonautica.II.987-992

[6] Hedreen.1994

Cite This Work

To export a reference to this article please select a referencing stye below:

Related Services

View allDMCA / Removal Request

If you are the original writer of this essay and no longer wish to have your work published on UKEssays.com then please click the following link to email our support team:

Request essay removal